Sexual violence against enslaved men and women was common during slavery, as enslavers and White people used their positions of power to abuse. Historically, this widespread violence was ignored or minimized. In interpreting a community’s story of slavery – like the history of Raleigh and its residents during the time of the Capitol’s construction – it is evident that sexual violence against enslaved people almost certainly occurred. For historians working to piece together each person’s narrative, the intergenerational trauma of this violence shows up in both concrete and intangible ways.

Most frequently, enslaved Black women were the victims of sexual abuse and harassment. The laws of the United States both established and protected slavery, and violence against enslaved Black people and especially Black women, was often not criminalized. Additionally, this form of violence (either in practice or the threat) was one of many forms of control used by enslavers to ensure obedience and compliance by those they held in bondage. An enslaved woman had no legal recourse or protection against the sexual advances of any White person, including their enslaver, overseers, or any other White man or woman. The sexual abuse of women and girls under slavery ranged from verbal harassment and expressions of desire to repeated sexual assault by White people. Many of the violent White male oppressors were smaller scale enslavers and overseers, but some were extremely prominent enslavers. Famously, Thomas Jefferson, one of the nation’s founding fathers, an early president, and the framer of the Declaration of Independence, repeatedly sexually assaulted Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, beginning when she was a teenager.

Of her abuser Jacobs said, “For my master [...] had just left me, with stinging, scorching words; words that scathed ear and brain like fire. O, how I despised him! I thought how glad I should be, if some day when he walked the earth, it would open and swallow him up…”

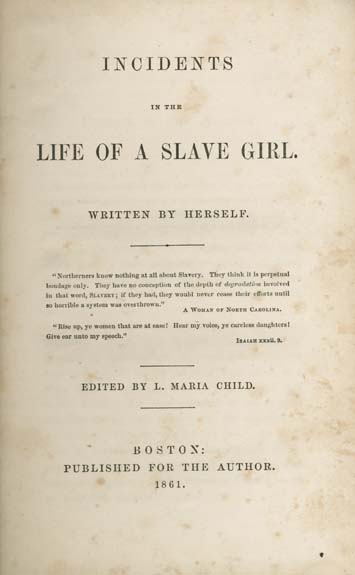

One documented case of sexual violence against an enslaved woman in North Carolina is that of Harriet Jacobs. Jacobs was born an enslaved person in Edenton, NC in 1813. Inherited by Mary Matilda Norcom, she was brought under the control of Dr. James Norcom, Mary Matilda’s father. Jacobs was subjected to sexual abuse from Norcom, which she ardently resisted. Eventually, Jacobs fled and hid in the attic space of her grandmother’s home for almost seven years before self-emancipating. In 1853, she documented both the abuse she suffered and how she escaped in the book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Of her abuser Jacobs said, “For my master […] had just left me, with stinging, scorching words; words that scathed ear and brain like fire. O, how I despised him! I thought how glad I should be, if some day when he walked the earth, it would open and swallow him up…” Her narrative was the first to speak about this type of violence against enslaved people.

The rape of enslaved women by White men frequently resulted in the birth of multiracial children. Any child born to an enslaved mother was, by law, automatically enslaved themselves. Official US census records point to the likely scale of the rape of enslaved Black women by White men. The 1850 census reported 406,000 Americans as “visibly mulatto” – an offensive historic term used to note someone of both African and White European ancestry. This number means almost 11 percent of the African American population at the time showed Black and White parentage, giving an indication of the likely scale of these offenses. W.L. Bost, a formerly enslaved person from North Carolina, noted in a WPA interview in 1937 that, “Plenty of the colored women have children by the white men. She know better than to not do what he say. Didn’t have much of that until the men from South Carolina come up here [to North Carolina] and settle and bring slaves. Then they take them very same children what have they own blood and make slaves out of them.”

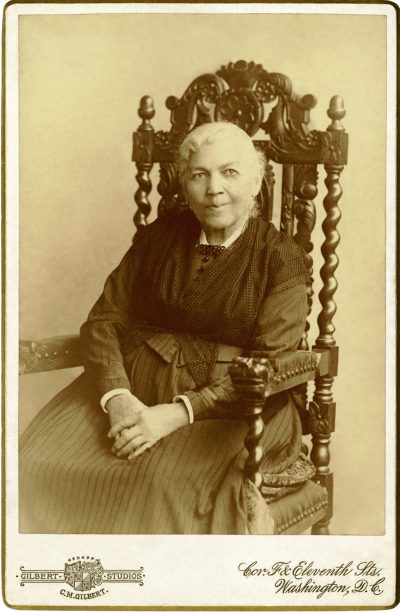

Famed author, scholar, and activist Anna Julia Cooper, whose enslaved grandfather helped construct the Capitol noted, “I was born in Raleigh North Carolina. My mother was a slave and the finest woman I have ever known. Presumably my father was her master, if so I owe him not a sou [sic]. She was always too modest and shamefaced ever to mention him.” (To read Anna Julia Cooper’s A Voice From the South)

With the case of Ned Peck, who worked on the construction of the Capitol, historians theorize that Ned was biracial. On the 1850 federal census slave schedule, his enslaver William Peck’s enslaved people are entirely listed as “M” for “mulatto,” except for one young girl, who is listed as “B” for “Black.” If Ned was acknowledged as biracial, it was possible that his father was White, or one or both of his parents was biracial. His father could have been his enslaver – it was common for enslavers to enslave their own biological children. (For more information about Ned Peck)

Sexual violence against enslaved people could also include other instances of violence and degradation. William Anderson, author of Life and Narrative of William J. Anderson, Twenty-Four Years a Slave (1857) noted the following, “My master often went to the house, got drunk, and then came out to the field to whip, cut, slash, curse, swear, beat and knock down several, for the smallest offense, or nothing at all. He divested a poor female slave of all wearing apparel, tied her down to stakes, and whipped her with a handsaw until he broke it over her naked body. In process of time he ravished her person and became the father of a child by her. Besides, he always kept a colored Miss in the house with him. This is another curse of Slavery ⎯ concubinage and illegitimate connections ⎯ which is carried on to an alarming extent in the far South.”

Another type of abuse, especially against enslaved Black women, was carried out by wives of enslavers. White women could react to instances of White men assaulting enslaved women by punishing the victims of their husband’s violence. In a WPA narrative, Richard Macks, who was enslaved in Maryland recalled, “There was a doctor in the neighborhood who bought a girl and installed her on the place for his own use, his wife hearing it severely beat her.” In his autobiography Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, Solomon Northup wrote of Patsey, a woman he knew while she was enslaved on a Louisiana plantation. Northup observed the ire Patsey experienced from her enslaver’s wife, even as Patsy was the victim of sexual assault from her male enslaver. Of Patsey, Northup wrote “If she was not watchful when about her cabin, or when walking in the yard, a billet of wood or a broken bottle, perhaps, hurled from her mistress’ hand, would smite her unexpectedly in the face.”

Though it was significantly underreported (when sexual violence was already not often reported or acknowledged), enslaved men and boys also suffered sexual abuse and assault from White male enslavers. We know this through a handful of sodomy cases that ended up in courts. As early as the 1600s, Nicholas Sension of Connecticut was in court for sexually preying upon men he enslaved.

Black men also suffered from the sexual abuse of their female relatives and relations, as they felt powerless and unable to protect the women they knew and loved. According to historian Deborah Gray White, “Those who tried to protect their spouses were themselves abused.” Men were often affected psychologically by the lack of control, with one formerly enslaved person Lewis Clarke declaring that an enslaved person “can’t be a man” because he could not protect his female relatives from sexual advances. Sam and Louisa Everett, who were enslaved in Virginia, noted in a WPA narrative that “Sometimes [enslavers] forced the unhappy husbands and lovers of their victims to look on [while assault occurred].”

References:

- Census Of The United States, 1830-50, Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census, The National Archive, Washington, D.C.

- Cooper, Anna Julia. A Voice from the South. Xenia, Ohio: The Aldine Printing House, 1892. Accessed on DocSouth.unc.edu.

- Feinstein, Rachel A. When Rape was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery. Routledge, 2018.

- Fischer, Kirsten. Suspect Relations: Sex, Race and Resistance in Colonial North Carolina. Cornell University, 2002.

- Foster, Thomas. “The Sexual Abuse of Black Men under American Slavery.” Journal of the History of Sexuality. University of Texas Press, 2011.

- “Handwritten Biographical Sketch” (2017). Biographical Data. 8. https://dh.howard.edu/ajc_bio/8. Anna Julia Cooper, Anna Julia Cooper papers, courtesy of the Moorland-Spingard Research Center, Howard University.

- Jacobs, Harriet. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- “Letters to R. C. Ballard regarding slave woman abuse.” From PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h3436.html

- “On Slaveholders’ Sexual Abuse of Slaves, Selections from 19th & 20th century Slave Narratives.” From National Humanities Center, Resource Toolbox: The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/enslavement/text6/masterslavesexualabuse.pdf