A commonly held impression by non-historians is that White women did not actively participate in slavery – that they merely were bystanders to the actions of White men. Earlier historians depicted women as “fictive widows,” “deputy husbands,” or “fictive masters,” claiming that women were only acting as stand-ins to male enslavers. Historians thought that if women did have excessive contact with enslaved people, it was from a domestic perspective, as women were the keepers of the household. Traditionally, historians also assumed that women were at least somewhat insulated from the brutality and violence of slavery by their secondary status to men. Many historians believed that a woman’s financial independence was entirely dependent on her husband, as laws prevented women from much autonomy. This was – of course – not true. White women brought their own finances into marriages and at times were even the more financially secure partner.

Newer scholarship shows that White slave-owning women were the norm rather than the exception. White girls were trained as enslavers, sometimes from birth.

Parents willed enslaved people to daughters, as slave owning was a way for women to gather and control wealth. White girls grew up alongside the people they enslaved, knowing their role as enslavers and exercising their power accordingly. According to historian and author Stephanie Jones-Rogers, these women were as invested in slavery as White men and assumed roles in “buying, selling, and disciplining” enslaved people. Jones-Rogers also states that “slave owning women not only witnessed the most brutal features of slavery, they took part in them, profited from them, and defended them.”

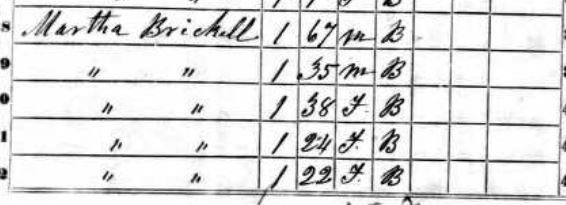

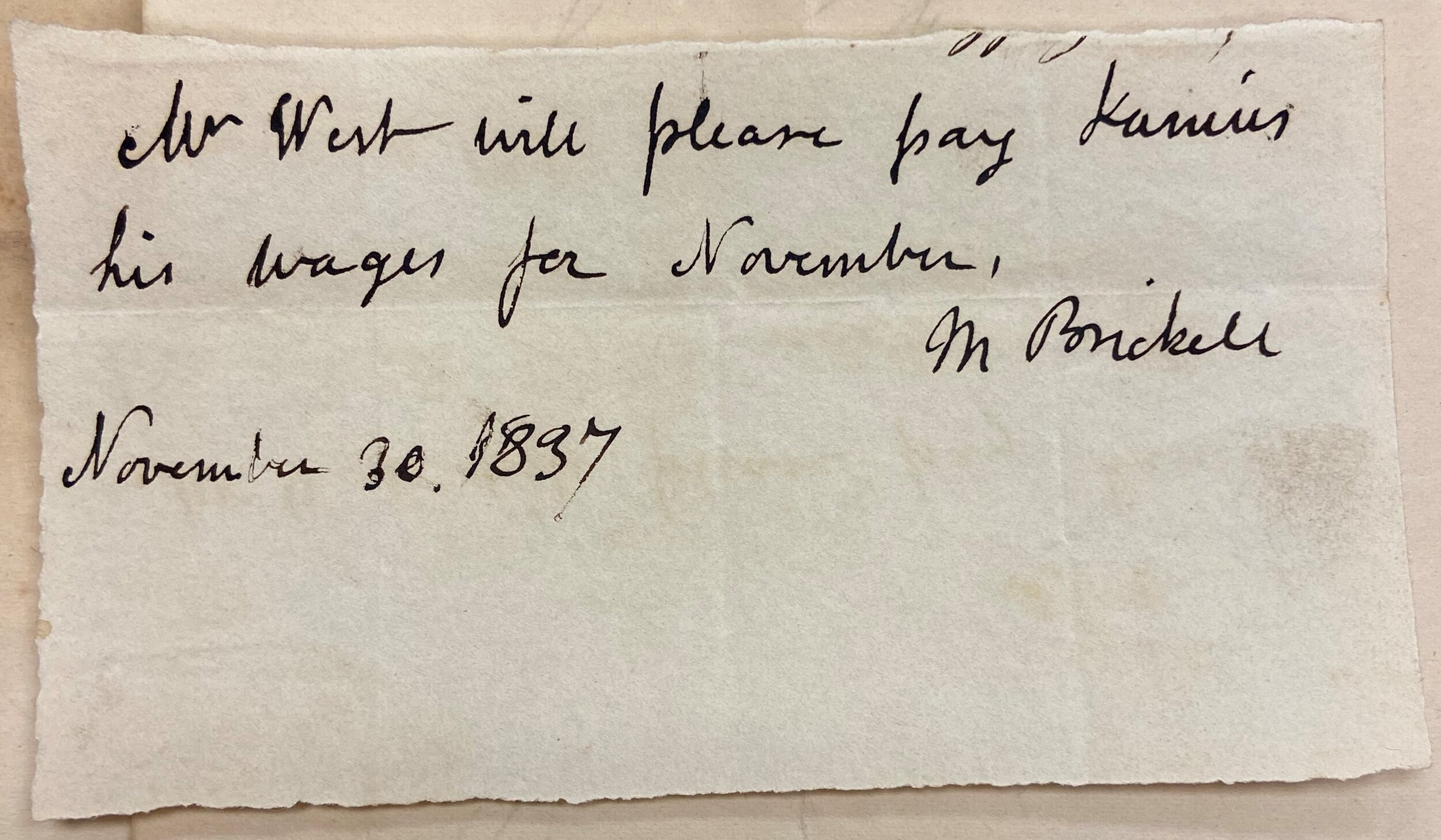

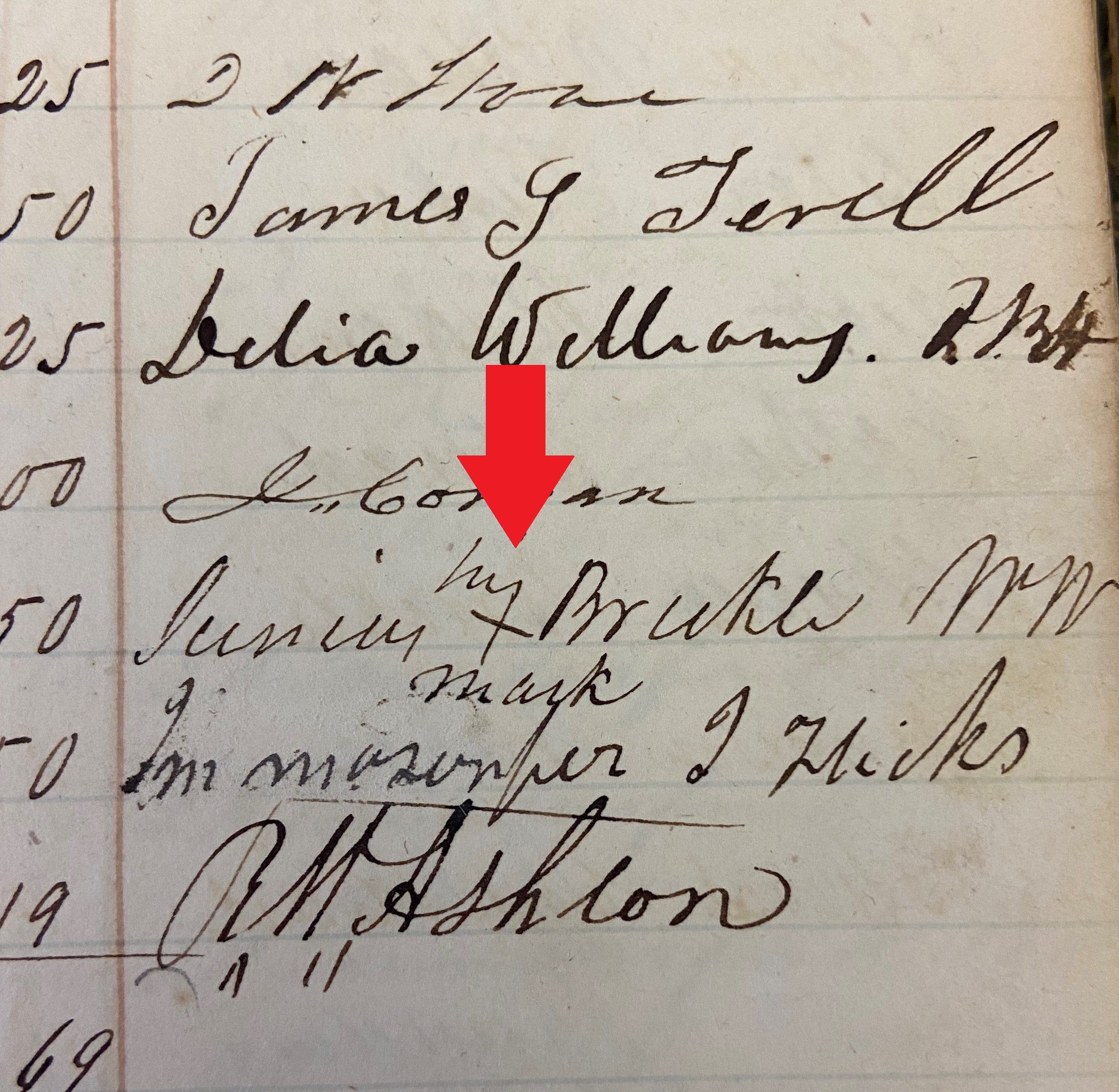

Most narratives written from the perspective of enslavers come from people who enslaved many individuals. However, these were a small minority of enslavers, and the typical woman enslaved fewer than ten people. Some women who hired out enslaved people to the Capitol project fit into this description. Martha Brickell – who enslaved Junius Brickle – probably enslaved around 8-10 people for most of her life. Martha was born in Wake County in 1778, the daughter of Colonel Joel Lane, who in 1792, sold 1000 acres to the state of North Carolina as a site for the city of Raleigh. In his will, entered into Wake County records in 1798, Joel Lane leaves to his “Daughter Martha Lane, her heirs and assigns forever the following Negroes VIZ Sam, Phill, Sally Nansey and their future increase.” Upon Joel Lane’s death in 1795, a 17-year-old Martha inherited several enslaved people. Martha’s two husbands died in the early nineteenth century, and it’s possible that Martha inherited enslaved people from them upon their deaths – both men are shown enslaving multiple people in the 1800 census. But for much of her life, Martha was single and made money from hiring-out enslaved people, a common practice for female enslavers. Martha died in 1852 and, continuing the practice of willing enslaved people, she left a “negro girl named Harriet about two years of age” to her daughter-in-law. (For more information on Junius and Martha)

Mary Wheaton also hired out a laborer to the Capitol project – Alfred Wheaton in 1838. Born around 1787, Mary was an enslaver and a property owner in Raleigh by the 1830s. Her husband died in 1832. The 1840 census shows her living in Wake County with six total enslaved people. In the 1850 census, Mary is shown with enslaved people and also living with two young White girls, Mary Barba and Patty Harde, ages 8 and 9 respectively. Mary died in 1863, and her will details that twelve enslaved people, including Alfred, along with Jacob, Moses, Jim, Martha, Leon, Patience, Adeline, Ellen, Antoinette, and Corinna are to be left to Mary’s niece. Mary’s husband was dead and there is no indication that she had children of her own, a situation that made the financial benefit of hiring out enslaved people crucial. (For more information on Alfred and Mary).

Delia Haywood was less typical of a woman enslaver. When Delia’s husband Stephen Haywood, a member of the prominent local Haywood family, died, she inherited great wealth and the power of his estate. This estate included probably hundreds of enslaved people. By 1830 Delia lived in Raleigh and is listed as an enslaver there with eighteen enslaved people, and as an absentee enslaver in other parts of Wake County. This shows that she probably owned property elsewhere and operated a plantation there. She hired out multiple people to the Capitol project, including Abraham, Cato, Moses and probably Henry. In 1850, she enslaved fourteen people in Raleigh and was also listed as the absentee enslaver of nine people in the St. Marie’s District of Wake County. Delia pursued enslaved people when they sought freedom. Delia or someone acting on her behalf placed at least four runaway slave ads. In an ad from 1828, Delia notes that Davy has run away and mentions “the mark of the cut of a knife on one of his cheeks, 2 or 3 inches long.” When Cato Haywood, who worked on the Capitol project, sought freedom in 1837, Delia stated that “Cato is of the ordinary size, very black complexion, and has also lost some of his front teeth; when spoken to, has rather an impertinent way of expressing himself.” In these instances Delia notes a physical abnormality (the cut in Davy’s cheek) and conduct (the way Cato was seemingly “impertinent” to her). Both suggest Delia was regularly acting with violence against her enslaved people. In another ad placed for Moses from 1844, the placer of the ad, Thomas Ormond notes that he hired out Moses from Delia for the year. The Capitol’s records indicate that Delia routinely hired out her enslaved people to generate income. Delia died in 1852 and her estate papers list many enslaved people including Charles, Miles, Becky, Sampson, Sam, Sally, Henry, Mary, Sarah, Amy, Jordan, Phil, Lotty, William, Lucy, John, and Tom. (For more information on Cato and Delia)

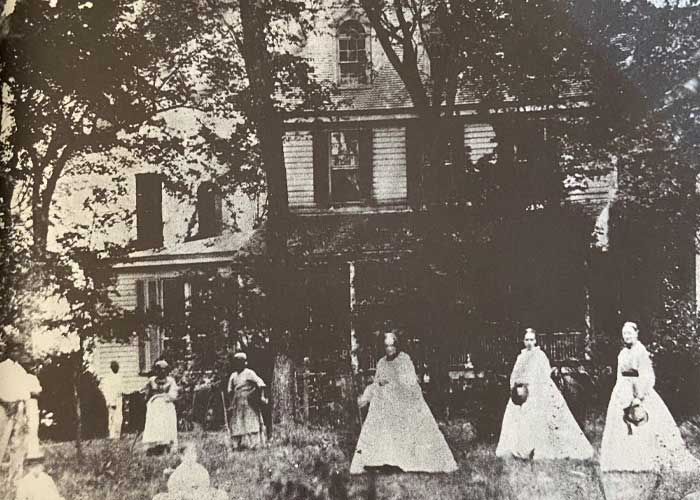

Sarah Stone was another enslaver compensated during the Capitol’s construction. In her lifetime, Sarah enslaved dozens of people. Sarah was the second wife of David Stone, who served as Governor of North Carolina from 1808-1810. After they married in June of 1817, they resided mostly at Restdale, the Stone plantation in Wake County, located ten miles from downtown Raleigh. David Stone died in 1818, and Sarah continued to live in Wake County, either at Restdale or at property she owned in downtown Raleigh. During this time, she made money by hiring out enslaved people. She enslaved at least four people who worked on the Capitol – Giles, Ceaser, Reuben and Robin. In 1830 she appeared on a list of absentee enslavers – with forty-one enslaved people in Marks Creek District in Wake County. When Sarah Stone died in 1838, forty-six of her enslaved people were sold at auction, in accordance with her will. (For more information on Giles and Sarah)

Of the dozens of enslavers involved in the Capitol’s construction, a significant portion were women. The state of North Carolina compensated these women for hiring out enslaved people to the Capitol project. (For more on the building’s construction and “hiring out”)

References

- Capitol Building records. State Archives of North Carolina

- “Elmwood,” Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Agriculture and Environment, 1800-2004, Olivia Raney Local History Library Repository, Wake County Public Libraries

- Jones-Rogers, Stephanie E. They Were Her Property: White Women As Slave Owners in the American South. Yale University Press, 2019.

- North Carolina Runaway Slave Advertisements Digital Collection.

- State Capitol Construction Records, Treasurer’s and Comptroller’s Papers. State Archives of North Carolina.