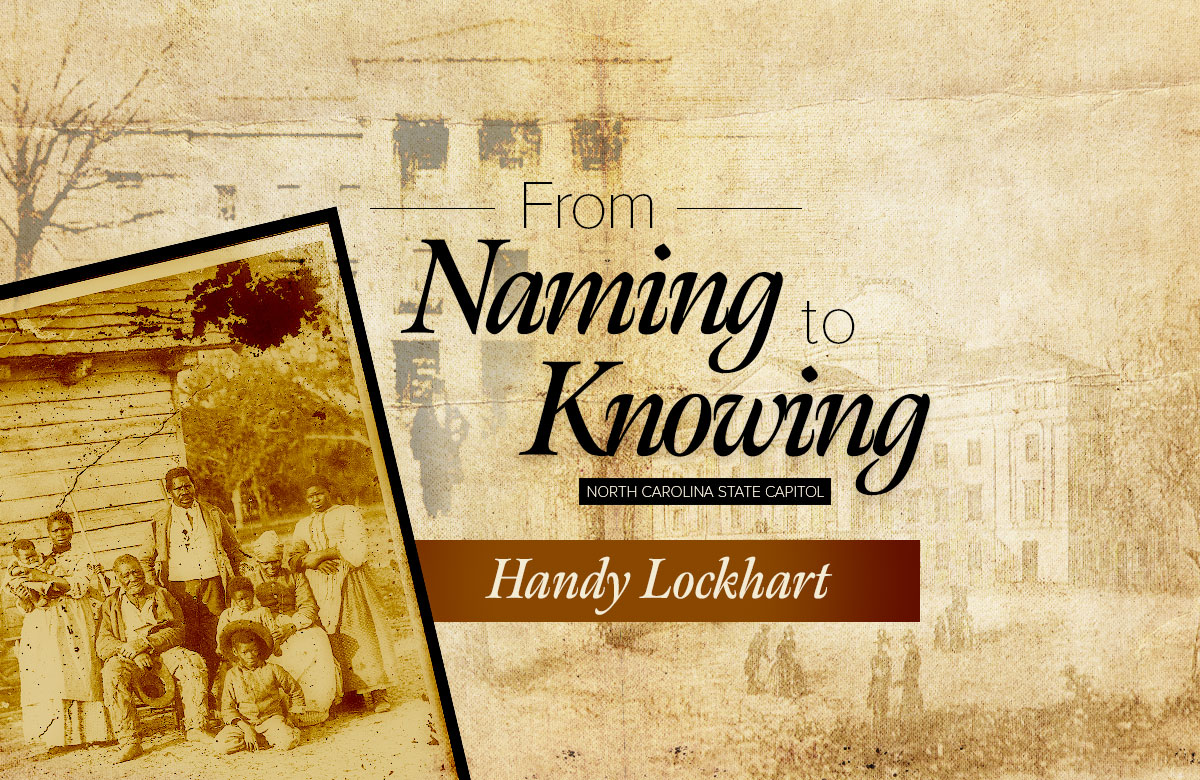

Cabinetmaker Handy Lockhart (sometimes recorded as “Lockett” or “Locket”) helped craft more than 170 pieces of furniture, namely desks, chairs, and tables, for use in the House and Senate Chambers. Few records have been located that give insight into Lockhart’s life while in bondage. However, a wealth of primary and secondary sources reveal that he was a well-connected, politically active man of faith in the years after he gained his freedom. Lockhart is not named in the 1834 Commissioners Report on the Capitol construction.

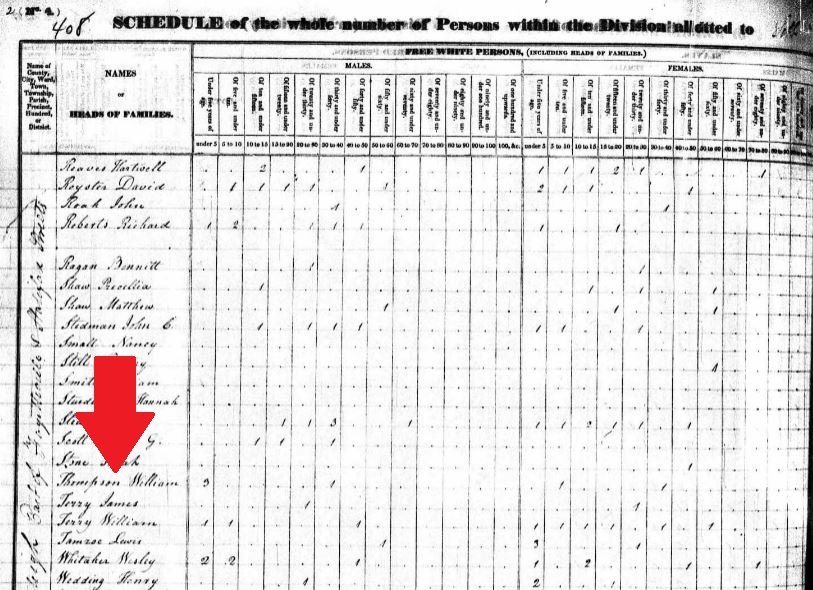

Later census records show Handy was born in North Carolina around 1795. He may have been born in Raleigh or come to the city as a child. Lockhart’s enslaver, William Thompson, was born in New York in 1798. The date of his relocation to Raleigh is unknown, however, the 1830 census recorded that Thompson lived in Wake County and enslaved nine people at that time.

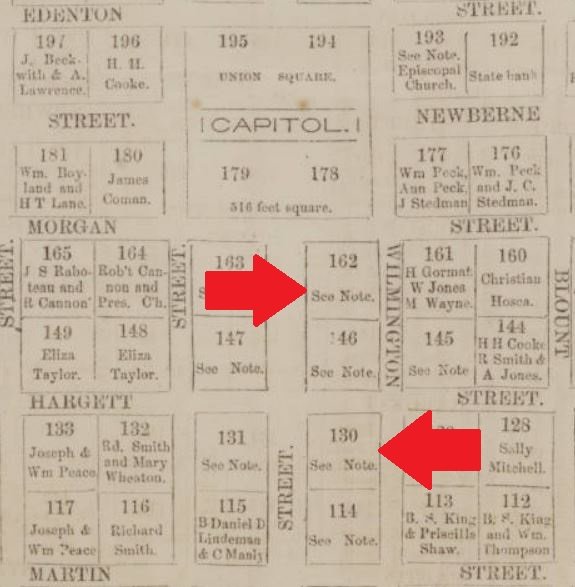

By 1834, Thompson, a cabinetmaker by trade, owned land in Raleigh and was operating a furniture shop near the southeast corner of Union Square.

In 1839, the state hired Thompson to construct the legislative furniture for the new Capitol, and he brought his enslaved men to the project with him. A recollection by NW West printed in the Raleigh Farmer and Mechanic newspaper in 1911 mentions Lockhart, saying “On a back street on this block a Mr. Thompson had a cabinet shop. I was told that he and a negro man…Handy Lockhart, and some other negro slaves under his direction made all the furniture – solid mahogany – now in use in the House of Representatives.” If primary sources detailing Handy’s work on the legislative furniture in the 1830s exist, they have yet to be located.

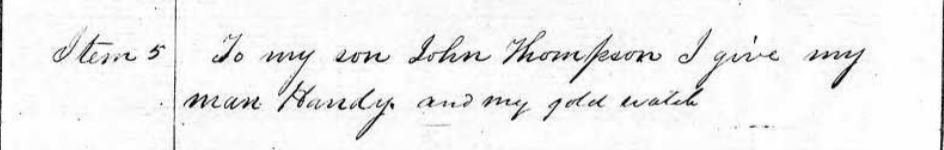

We assume Handy Lockhart did not gain his freedom until General Sherman’s troops occupied the city in April 1865. William Thompson’s 1855 will bequeathed “to my son John…my man Handy and my gold watch…” Thompson lived until 1869 and appears to have not updated his will, meaning the 11 enslaved people he claimed on the 1860 Federal Census slave schedule and those mentioned by name in his will were freed when slavery was abolished prior his death.

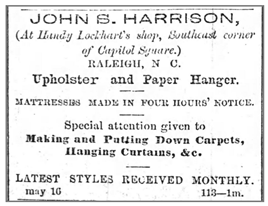

Handy Lockhart seems to have continued working in the shop once owned by William Thompson near the Capitol until at least 1870.

Lockhart was also later employed by Henry J. Brown. Like Lockhart, Brown was a cabinetmaker, and in 1836 he established the H.J. Brown Coffin House at the corner of Dawson and Morgan Streets. Brown’s business eventually evolved from building caskets into a full service funeral parlor as the practice of embalming the deceased’s body gained widespread acceptance after the Civil War. Handy’s work with Brown appears to have led him to move from building coffins to other aspects of the funeral business, as numerous sources (including city directories) list Lockhart’s occupation as an undertaker.

Though the extent of Brown and Lockhart’s relationship is not known, Brown and his wife Lydia sold Handy a parcel of land in Raleigh in October 1868. Lockhart paid $450 cash for ⅛ of an acre (part of Lot 63) located on Blount Street near the intersection at Davie. Handy maintained a home and shop at 409 S. Blount Street for the rest of his life. The General Index to Deeds, Mortgages and Real Estate Conveyances for Wake County shows he purchased additional small tracts of land in 1874-75, gradually increasing his assets through property ownership.

Lockhart also purchased two different parcels of land in Oberlin Village, to the west of Raleigh. Oberlin Village originated as a freedman’s village, established by newly emancipated African Americans. The area became a thriving enclave for the middle class Black community. Handy Lockhart initially bought land in Oberlin from the estate of Richard Shepard [the grandfather of Dr. James Shepard, who would go on to become one of Oberlin’s most well-known residents. Dr. Shepard founded what is today NC Central University in Durham, NC.]. His first purchase of land was near where the state fairgrounds once stood, across Hillsborough Street from present day NC State University. In 1881, Lockhart bought more land in a newer section of Oberlin known as San Domingo, which was situated north of Wade Avenue near Baez Street and Grant Avenue.

Though it doesn’t appear that Handy ever lived in Oberlin Village himself, he included the following provision in his will: “I will and devise to my beloved daughter Louvina one house and lot in the Village of Oberlin near the city of Raleigh…containing one fourth of an acre more or less to have and hold during her natural life, and at her death, to her two daughters Mary and Thena [Berthenia] Lockhart.” The city directory from 1899 lists Louvina as living in Oberlin, working as a laundress and the 1900 census denotes she owned her home.

Given his work in constructing the Capitol furniture, it is not surprising that the state regularly hired Lockhart to make repairs to those pieces. State Auditor’s Reports from various years list payments made to Handy, now a free man, for tasks such as “sundry repairs on desks and chairs in Senate Chamber and House of Representatives” and for “making [a] book case for Supreme Court room; also for sundry repairs in the different rooms of the Capitol,” for which he was paid $70.75 in 1873.

Handy’s repair work on the Capitol furniture was held as an example of the “corruption” of the Reconstruction legislature in a local newspaper on one occasion. The Raleigh Weekly Sentinel, a mouthpiece of the conservative Democratic Party, published a column in early 1871 titled “Auditor’s Report.”

I serve out to-day, another mouthful from this olla podrida, cooked by our Radical administration for the delicate palates of the tax payers of the State. In looking over the Report of the State Auditor, in a tabular statement of expenditures in detail, we find that uncle Handy got the following sums for the services mentioned.

[expenditures listed]

…Making in the aggregate the sum of five hundred and eighty four dollars and fourteen cents paid to Handy, mostly for repairing chairs in the two Halls. The Radical Legislature must have been a terrible set for breaking chairs, taking the above charges as a criterion to judge by. We daresay that the most rowdy drinking establishment in Raleigh, or even New-Bern, didn’t have as much breakage among its furniture between Oct. 1st 1869 and Sept. 30th 1870.

The column was presumably written by Josiah Turner Jr., the owner and publisher of the Sentinel. Turner succeeded in using his paper as a platform to publicly undermine the progress made during Reconstruction. The newspaper was a vital tool in aiding Democrats win back a majority in the General Assembly and for the overthrow of Governor William W. Holden in 1870 and his impeachment in 1871. As a well-known and politically active Black citizen, Handy Lockhart was a frequent target of the city’s conservative newspapers.

Civic Leadership

In the 1860s and 70s, Lockhart seized the opportunity to help shape life for his community by taking an active role in local politics. He rose to become a well-known figure within the young Republican party in a short period of time. Although the extent of their personal relationship is not known, Handy Lockhart’s name often appears alongside that of James Henry Harris. Harris emerged as one of the most prominent and effective Black politicians in the state during this time period and helped found the NC Republican Party. He was elected to the 1867 constitutional convention and served in both houses of the state legislature between 1868-83.

In October 1866, Lockhart (recorded as “Locket” in the minutes) served as a Wake County delegate to the second Freedmen’s Convention, held at St. Paul AME Church in Raleigh. Lockhart was appointed to both the Committee on Rules and the Business Committee. The Business Committee took charge of inviting speakers to address the convention. Notably Governor Jonathan Worth and former Governor William Holden accepted invitations and spoke to those gathered in the church sanctuary. The Business Committee also drafted and presented an “Address of the Freedmen’s Convention to the White and Colored Citizens of North Carolina” which called for enfranchisement and equal rights for Black North Carolinians.

The delegates of this convention called this body the North Carolina State Equal Rights League. Headquartered in Raleigh, the stated purpose of the League was “to secure, by political and moral means, as far as may be, the repeal of all laws and parts of laws, State and National, that make distinctions on account of color.” The League aimed to prioritize the establishment of schools for the children of freedmen. Handy Lockhart was elected by the body to serve on the seven member Educational Association, which set about to “aid in the establishment of schools, from which none shall be excluded on account of color or poverty and to encourage unsectarian education in this State especially among the freedmen.”

In the spring of that year, Lockhart and eight other Black men appealed to the NC General Assembly to incorporate the “Colored Educational Association of North Carolina.” The all-White legislature approved the act, thus giving the Educational Association the “power and purpose of establishing Schools and encouraging and promoting generally Education among the colored children of the state, and may, for such purpose, receive donations and acquire and hold estate of any kind, not exceeding one hundred thousand dollars in value.”

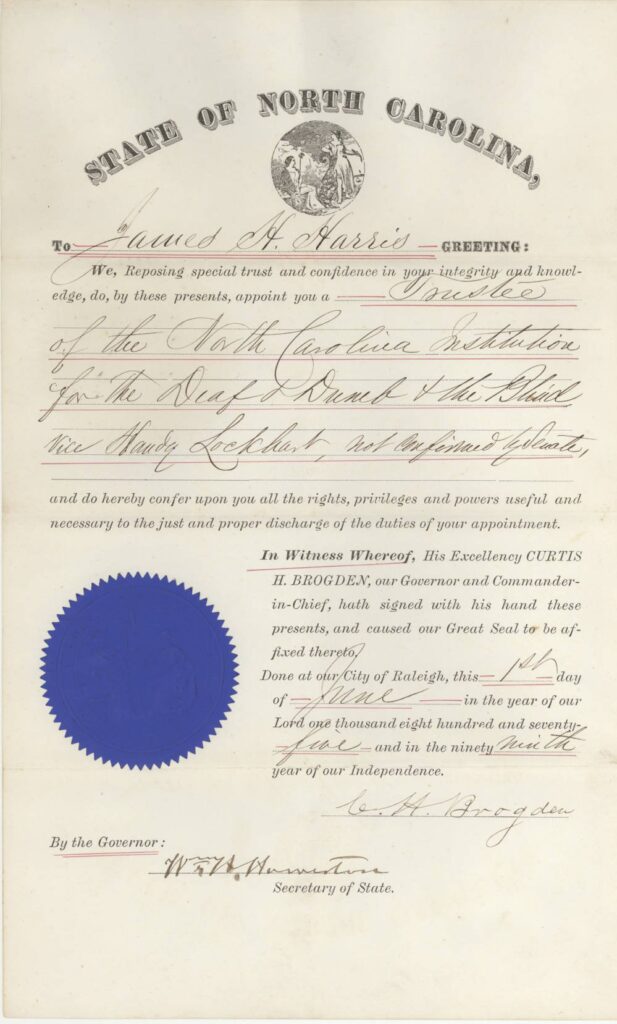

This would not be Lockhart’s only foray into working to ensure an education for marginalized people. In 1872, Governor Tod R. Caldwell appointed Handy to serve as a trustee for the NC Institution for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind. Though the state Senate confirmed the appointment with 27 votes to 12, some White citizens expressed anger that a Black trustee would have any authority over an educational institution that served a majority of White students, though Black students (separately) attended as well. A brief history of the institution, published 20 years later in 1893, made a point of mentioning Reconstruction-era appointments to the Board. While Handy is not named in the report, his service is snidely noted: “About this time, the Governor appointed a board, among whom was one negro who could not sign his own name. Under such management were our unfortunate children placed for their physical, mental, moral, and spiritual instruction.” Lockhart was re-appointed and confirmed again in 1873 and 1874. It was during Lockhart’s tenure that the school’s trustees oversaw the construction of a new separate building for Black students. In 1875, James Henry Harris replaced Lockhart on the Board. Harris’ certificate of appointment is held in his papers at the State Archives of North Carolina and Lockhart’s name appears on the certificate as Harris’ vice.

In addition to serving at the state level, Lockhart also gained numerous city appointments. Under the Reconstruction government in 1868, Governor William Holden appointed new municipal officials to serve Raleigh. In selecting members of the Raleigh Board of Commissioners, Holden appointed the first Black men to serve in those roles: Handy Lockhart to represent the east ward and James Henry Harris for the west ward. Lockhart also ran for Raleigh mayor in 1872 and served several terms as magistrate. At the start of the 1883 session of the NC House of Representatives, Lockhart was nominated to serve as Assistant Doorkeeper, although he came in second in a three way vote (80-18-3).

A Meeting with the President

While James Henry Harris became a nationally known Reconstruction-era political figure of some renown, Handy Lockhart’s reach was decidedly more local. However, in January 1867, Lockhart and Harris traveled to Washington, D.C. to serve as North Carolina’s delegates to the National Equal Rights League Convention of Colored Men, held over three days. At this meeting, Harris was elected as the Vice President of the national organization.

A week after the convention, Harris and Lockhart met with President Andrew Johnson. A writer from The New York Times reported on the meeting in some detail and the article later ran in the local Raleigh papers. Lockhart isn’t named in the article and is instead referred to as “Mr. Harris’ friend.” However, it would seem that Lockhart’s connections secured the meeting with the President, rather than Harris’. On January 8, 1867, William Thompson, Lockhart’s former enslaver, wrote the following letter to President Johnson:

Dear Sir,

The bearer of this Handy Lockheart visits the North on behalf of his Colored Brethren as well as his own gratification. He has been a servant in my family forty three years, and has at all times during this long period, devoted himself to the interest of myself and family, with all the energy he could command. He has enjoyed all the confidence and good feeling that could be bestowed by myself and family in return, which relation has not been attended by what has taken place by obtaining his freedom during this long period of servitude on no one occasion has there been cause of any kind to find any fault in him it would be one of the greatest pleasures I could enjoy to call on you and take by the hand one who I believe has the honesty and hearty welfare of his Country’s good above all other worldly hopes or desires may you not be disap[p]ointed of your hopes.

I have a large share of sympathy for you in the great trials you must meet with in your exalted position as Chief of the greatest County that exists on the Globe if any opportunity should offer me I shall most certainly embrace it to gratify a desire much at heart this desire is evinced by the circumstances of the slight acquaintance I had with your early boyhood as I was a next door neighbor to you in the year 1819 I have not nerve sufficient to say any thing to you about these misguided people in those sorely afflicted part of the Country who brought all these evils of Self suicide upon us be assured Sir my prayers for the whole of this Great Country and your desires.

With great respect I am again &c

Wm. Thompson

According to the Times account of the meeting, “Mr. Harris’ friend is about the same age as Mr. Johnson and they were raised together in Raleigh, N.C. Owing to this fact they found ready admittance to the presence of His Excellency, and enjoyed very favorable opportunities of obtaining free expressions of opinion from him.” The first part of the meeting involved pleasantries and reminiscing about life in Raleigh before President Johnson asked his guests about the protection afforded them by existing laws in North Carolina.

Harris responded, telling the President that the “present condition is anything but safe, and that they will never be fully guaranteed in their right as citizens without the power to vote for their friends and against their enemies.” Johnson expressed to his guests that he was “as much in favor of qualified negro suffrage as…anyone else of the Radical stripe; but in his opinion universal suffrage [would] effect more harm than good.” We are left to surmise how Lockhart and Harris responded, though they clearly pushed back on Johnson’s assertions. Johnson was reportedly “much gratified to learn that the freedmen of the South, who knew him personally, still retain their old regard for him, but was informed that they think they have good reason for disliking him politically now.” The President ended the meeting “with expressions of a hope by him that before long both blacks and whites will live along in tranquility, each race enjoying political rights in accordance with their respective merits.” Lockhart and Harris returned home to North Carolina to continue their fight for guaranteed suffrage and equal rights without the support they sought from the President.

The Lockhart Family

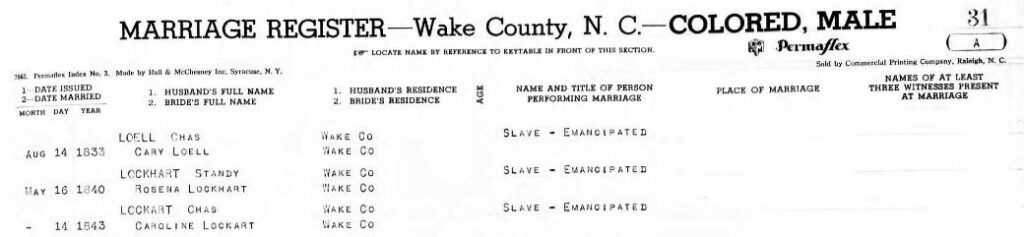

On May 16, 1840, just weeks before the new State Capitol’s grand opening, Handy Lockhart married Rosena Eaton (b. 1814). It is not known if Handy and Rosena were permitted to live together as man and wife prior to 1865, as their marriage had no legal status. The date of their marriage was later recorded in the Wake County Marriage Register following an 1866 law that legalized the marriages of formerly enslaved couples.

Together, the Lockharts raised five children – Louvenia, Bettie, Fanny, John, and Moses – all born between 1843 and 1860 prior to the abolition of slavery. As adults, the Lockhart sons followed in their father’s footsteps and both worked as cabinetmakers and undertakers. Louvenia and her children are listed in the 1870 census as living in the household of James Henry Harris, her father’s political ally. Louvenia worked as a cook in the Harris home. Fanny also remained in Raleigh and worked as a cook.

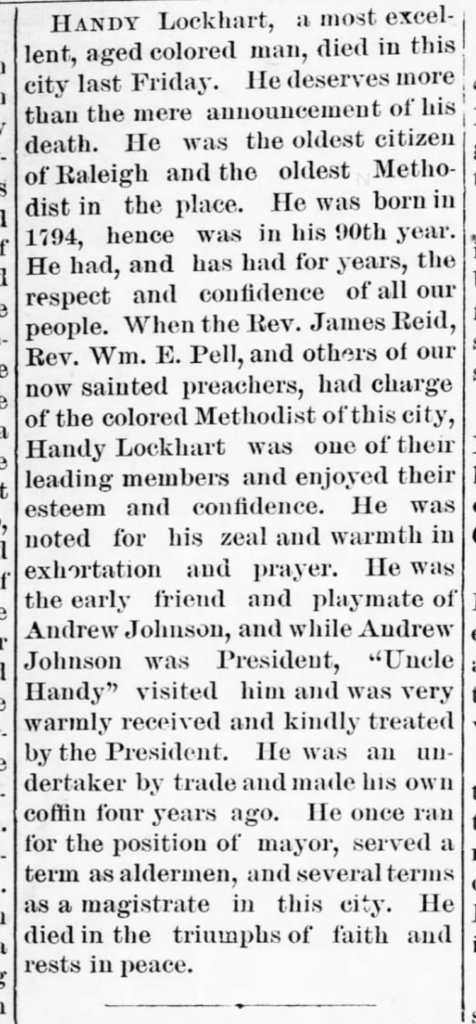

Handy Lockhart died on April 25, 1884, at his home on Blount Street. He was 89 years old. The News & Observer ran notice of his funeral, noting that “attendance was unusually large, evidencing the sincere regard in which the venerable man was held.” The paper lists his place of burial as Mt. Hope Cemetery, the city’s cemetery for African Americans. The records for Mount Hope Cemetery, along with those of other city operated cemeteries, were destroyed by fire in the 1930s and with them the knowledge of who was buried there and in what location. The newspaper listed his cause of death as paralysis, noting that he had fallen ill several days before.

Handy Lockhart parceled out his estate in a four page will that specified some very detailed directives. He left some furniture to Rosena and his daughters; to his sons “all the material…necessary to carry on the business of cabinet maker I leave to […] John and Moses Lockhart equally.” He then directed his executor to sell “all remaining perishable property for cash” and invest the proceeds in “some good real estate security” for a period of five years. Lockhart mandated that his family vacate the house on Blount Street so that the property could be rented to the highest bidder for a period of five years. The money collected from renting the house was to be invested as above. At the end of five years, all of the money from the investment was to be divided equally among Rosena (“should she then be living and not married”) and the children. The house and lot on Blount Street were also to be sold and the money divided among his surviving family members.

Despite the plans Handy made to care for his family after his death, probate court records show that Lockhart’s estate was not enough to cover his debts. Two acres of unimproved land in Oberlin were auctioned off in January of 1885. Records show that the other provisions of the will, including rental of his home, were followed after the $200 debt was paid from the sale of the land. The estate was closed in 1889, with a final balance of $246.14 to be distributed equally between Rosena (now living in Boston, MA) and the surviving children. Rosena died in 1899 at the age of 84 and is buried in Boston.

References:

- Certificate of appointment: James Henry Harris, Trustee for the North Carolina Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind, June 1, 1875. James Henry Harris Papers. State Archives of North Carolina.

- The Daily Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina). Thu, Jan 31, 1867.

- Executive and Legislative documents laid before the General Assembly of North Carolina (1874; 1875).

- The Farmer and Mechanic (Raleigh, North Carolina). Tue, Oct 17, 1911.

- Goodwin, E. The North Carolina Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind, Raleigh, North Carolina. 1845-1893. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections.

- Journal of the House of Representatives of the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina at its session of 1883.

- Letter from William Thompson to Andrew Johnson. Transcribed letter: Elizabeth G. McPherson (ed.), “Letters from North Carolina to Andrew Johnson,” North Carolina Historical Review, XXVIII (July 1951). Image of original letter.

- Little, M. Ruth. Historic Research Report for the Designation of Oberlin Village District as a Historic Overlay District. 2016

- Minutes of the Freedmen’s Convention, Held in the City of Raleigh, on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th of October, 1866.

- Mobley, Joe. Raleigh: A Brief History.

- The News & Observer (Raleigh, NC). Tues., April 29, 1884.

- Ninth Census Of The United States, 1870, Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census, The National Archive, Washington, D.C.

- North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. Microfilm. Record Group 048. State Archives of North Carolina.

- North Carolina US Will and Probate Records. State Archives of NC. William Thompson. 1855.

- Plan of the city of Raleigh first published in the year 1834. Map printed by Walters, Hughes and Company, Raleigh, N.C. From the book, Early Times in Raleigh Addresses Delivered by the Hon. David L. Swain, 1867. Accessed in the Raleigh History Collection, State Archives of North Carolina.

- Public Laws of the State of North Carolina, Passed by the General Assembly, at its session of 1866-67.

- Raleigh Christian Advocate (Raleigh, North Carolina). Wed, Apr 30, 1884.

- Raleigh City Directory, 1886.

- The Raleigh Daily Sentinel (Raleigh, North Carolina). Friday, September 8, 1876.

- Raleigh Hall of Fame website.

- Tenth Census Of The United States, 1880, Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census. The National Archive, Washington, D.C.

- Wake County Register of Deeds, 1785-1936. Microfilm. Book 27. Page 219.

- Weekly Sentinel (Raleigh), 1871.

- Will of Handy Lockhart. 5 September 1878. Wills and Estate Papers (Wake County).