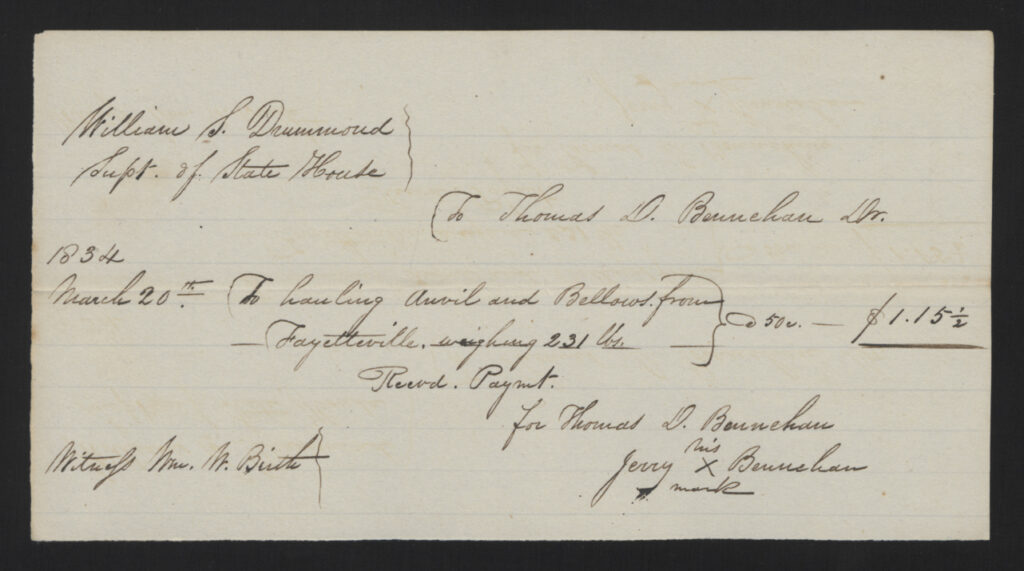

A wide variety of tasks meant different kinds of laborers were needed to carry out the construction of the Capitol. Sometimes commissioners or project managers tasked individual enslaved people with limited or one-time assignments like hauling materials. A receipt from 1834 noted that Thomas D. Bennehan received $1.15 for the work of an enslaved man named Jerry Bennehan. Jerry hauled an anvil and bellows from Fayetteville, North Carolina to the Capitol. (Both were tools used in blacksmithing; an anvil was used to shape, flatten or curve metal, and a bellows furnished strong blasts of air for a forge.)

Jerry was enslaved by Thomas Bennehan. In 1834, when Jerry appears in the archival record for hauling materials for the Capitol’s construction, he lived and worked at Stagville, a section of the large Bennehan and Cameron plantations. Jerry was a wagoner or wagoneer – a person who drove wagons – for the Bennehans. He frequently delivered letters to and from White family members, and moved crops and other items via wagon.

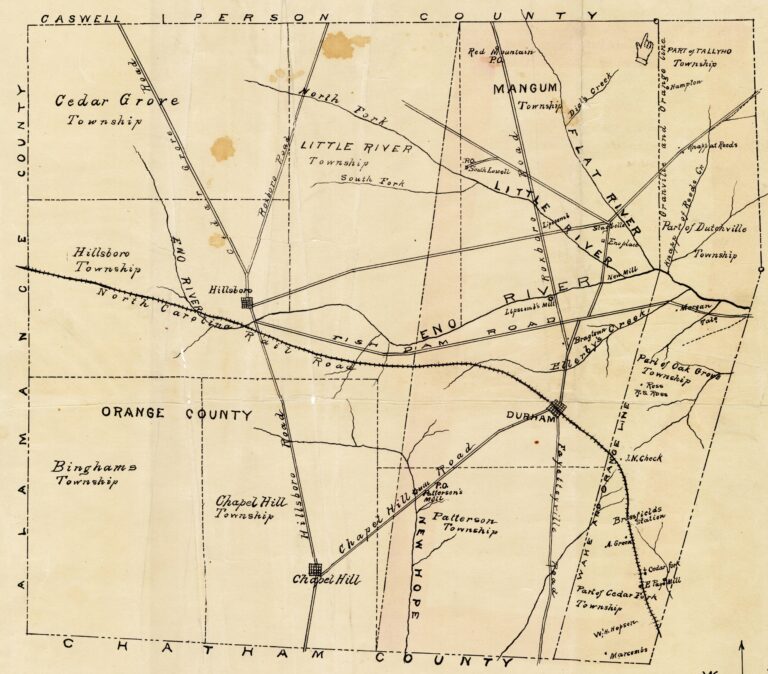

Stagville was around a day’s ride from Raleigh – one part of a vast North Carolina plantation complex in then Orange, now Durham, County. By the eve of the Civil War, almost 900 enslaved people lived at Stagville. After his father died in 1825, Thomas Bennehan inherited the Stagville property and Bennehan house. He lived there, managing the plantation until his death in 1847. (For more on Historic Stagville.) Thomas Bennehan probably purchased Jerry as an adult around 1806; Jerry is first mentioned in a 1806 Bennehan family tax list.

Jerry might have lived on the Stagville property immediately around the Bennehan house, as his work frequently put him in close proximity to the White Bennehan family. He could also have lived elsewhere on Bennehan land holdings. It’s possible Jerry was married twice (though the marriages of enslaved people were not legally recognized) and had at least one son. In the Bennehan’s records, there is an entry for a Jerry and a woman named Dilsy; the couple had a son named Elisha in May of 1811. Elisha died young, which could have been a traumatic experience for Jerry, especially since he was often traveling and away from his family as his work required. By 1824 letters to Thomas Bennehan mentioned “Jerry’s wife Milly,” but little is known about either woman.

As wagoner, Jerry often hauled to market whatever agricultural commodities Stagville produced. The plantations owned by the Camerons and the Bennehans produced wheat ground into flour. This product was hauled to places like Petersburg, VA and Fayetteville, NC to be sold, with a wagoner like Jerry doing much of that labor. He frequently carried cotton and tobacco, delivering these cash crops to Bennehan family contacts or business agents in these cities. He drove wagons from Stagville to Petersburg carrying multiple bales of cotton in 1833, 1834, 1835, 1836, and 1837. Sometimes this type of travel was risky to the products carried. In January 1833, Jerry “let one of the Barrels of Flour fall from the wagon which […] lost about 20 [lb].”

Sometimes as part of their assigned work, enslaved people traveled great distances away from the place where they or their enslaver lived. Enslavers used “slave passes,” which were written passes given to enslaved people to verify their travel and location. According to the North Carolina Slave Code of 1715, enslaved people were “required to carry a ticket from their enslaver whenever they left the plantation. The ticket stated where they were traveling and the reason for their travel.” Slave codes and slave patrols regulated the movement of enslaved people wherever they went. Though there is no evidence Jerry’s enslaver gave him a pass or a ticket, he might have carried such a thing with him as he traveled. Jerry’s task for the Capitol project required him to travel from Fayetteville to Raleigh. His work took him all over North Carolina and into Virginia on multiple occasions. Jerry’s position as a wagoner might have afforded him a few freedoms as he traveled alone, without direct supervision by a White enslaver or overseer. Along his route, he could have exchanged messages or news to other enslaved people he met, covertly traded, or bartered for other goods. However, alongside these freedoms, a network of White people still held Jerry under constant surveillance.

The Bennehan and Cameron families were prolific letter writers and mentioned Jerry in their correspondence. He frequently carried mail between members of the families, conveying news to various members. In a March 1816 letter from Rebecca Bennehan Cameron to her father Duncan Cameron, Rebecca mentioned that Jerry was in Petersburg, VA and that she had received family news from him.

Jerry is not named in the 1847 estate papers after Thomas Bennehan’s death, which probably meant Jerry died at Stagville in the late 1830s or early 1840s, as not many enslaved people were sold away from the property.

References:

- Bennehan, Thomas, Wills and Estate Papers (Wake County). State Archives of North Carolina.

- Cameron Family Papers. University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

- Cecelski, Vera. Site Manager Historic Stagville State Historic Site, Durham, NC. Interview, March 27, 2024.

- Map of Durham County, North Carolina. McDuffie, D.G. State Archives of North Carolina.

- Nathans, Sydney. To Free a Family: The Journey of Mary Walker. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2012.

- State Capitol: Miscellaneous Supplies, Hauling, and Services, Treasurer’s And Comptroller’s Records, State Archives of North Carolina.